Friction: A Double-Edged Sword

Tech blogging GOAT Ben Thompson wrote the following in 2013 as he was starting out Stratechery:

“...underlying everything is the seismic change that is only just beginning: if there is a single phrase that describes the effect of the Internet, it is the elimination of friction.

With the loss of friction, there is necessarily the loss of everything built on friction, including value, privacy, and livelihoods. And that’s only three examples! The Internet is pulling out the foundations of nearly every institution and social [sic] that our society is built upon.”

I remember having a lightbulb moment reading this for the first time, in my early 20s. To me, it was about much more than just delivery apps or social media – the elimination of friction was a framework I could build my life around.

Mobile + web 2.0 was an obvious area of friction-elimination: I could WhatsApp my relatives in Brazil, no longer having to purchase strange international calling cards over a landline; I could effortlessly save thousands of digital pictures on my phone, with no need for carrying clunky items on my person1.

But friction wasn’t just digital. There were opportunities everywhere to save time and make life more convenient – if taking an Uber was seven minutes faster and 100% less sweat-inducing than the subway, and some version of this mini-decision played itself out hundreds or thousands of times a year, then it was all the justification 25-year-old me needed to go and try to make more money, to fund friction-killing forever.

In my endless wisdom, I then married this philosophy with Naval Ravikant’s epic tweet storm of how to get rich (without getting lucky). Setting an “hourly rate” was the perfect antidote against having to return something at the store — a $20 refund was not worth 45 minutes of my time.

The point was hardcoded into my brain: friction is anathema to living a good life; make money to eliminate friction.

Alas, the kids don’t know shit.

Like every innovation, eliminating friction has a cost. In my case, it was somewhat meta: I took this approach so seriously that I turned into the classic “man with a hammer” – I thought every problem could be solved through the lens of friction-reduction/elimination2.

I realized friction could be reduced at the margins, and sure, it was convenient, but it was…marginal; it was a means to an end; it was a feature, not a foundation. Immediately jumping to friction-reduction-land was not in any semblance a way to view things by first principles. In fact, friction cuts both ways.

Jumping ahead to the present day, phones and apps have gotten so “good” that the topics du jour are no longer how convenient Amazon Prime is, or how fun it is to use Snapchat cat-ear filters, but much darker ones like Big Tech’s influence on rising rates of teen depression, echo-chamber driven political divisiveness and AI existentialism.

The elimination of friction is not the sole reason for all this darkness, but it’s no doubt a catalyst. As is the case with every technology, once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it’s not going back in. We’re stuck with streamlined, addictive digital services. The once whimsical “information highway” has no speed limit or traffic laws.

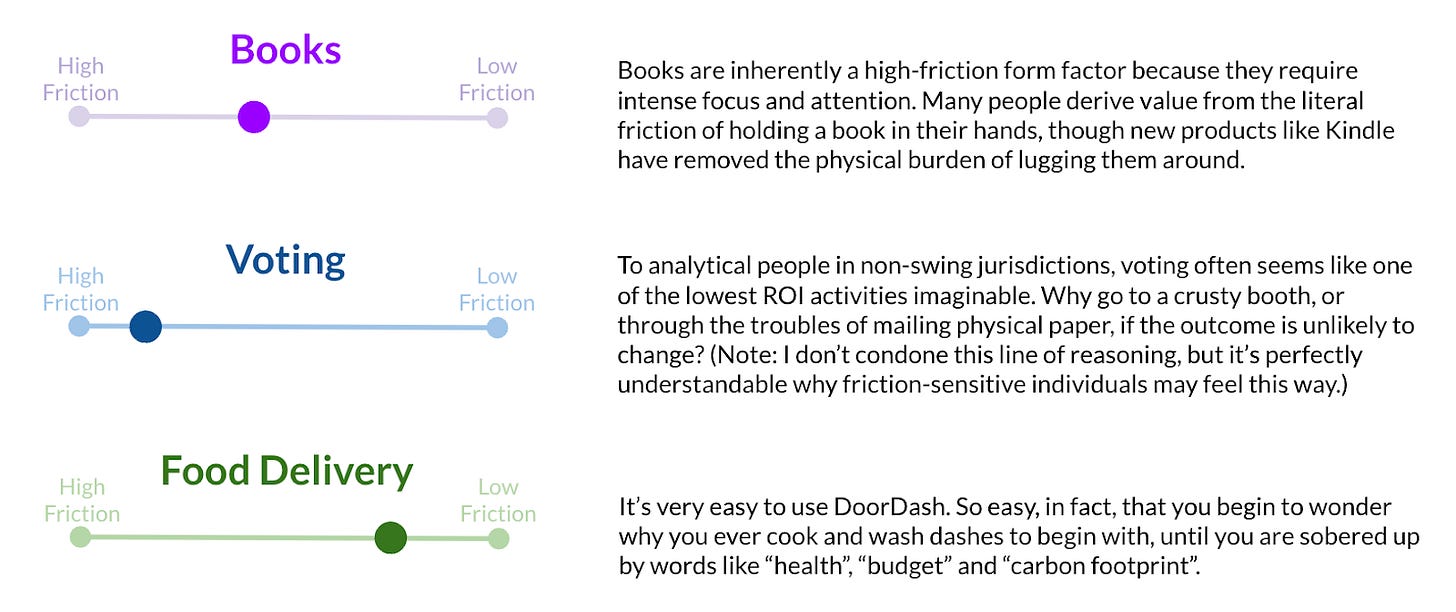

Modern consumer tech, that initial portal to zero-friction utopia, sheds light on the fact that the inverse of friction-elimination – ie, friction – can be a powerful tool. There are all kinds of real world examples where friction is intentionally built-in, both for positive and negative reasons.

Friction is a double edged sword. Its reduction, or elimination, can be useful for convenience and efficiency; unchecked, it can lead to adverse consequences. Furthermore, friction is a marginal phenomenon. It is a factor to consider when designing a system, not its foundational feature.

A year ago, floating through the universe of human intelligence that is the internet, I stumbled upon a beautiful image. I don’t know where I saw it; I just remember liking it (actually liking it, not clicking a button to signal that I liked it), snipping a copy and emailing it to myself. What the hell did people do back in the day when they read an article in the paper, and wanted to keep it for future reference?

If there is a single takeaway from this essay, it’s that we need to understand the nature of friction. Friction is everywhere; sometimes buried, sometimes intentional, sometimes in the perfect dosage to optimize flow.

The amount of friction baked into the products and services of the future will have deep consequences on technology and culture. It’s tempting to embrace the overarching design principles of our generation’s best products — to make things seamless.

But not all things are meant to be seamless. In fact, most important, human things require time, attention and effort. This is why there’s no point of automating family time or having a robot pet.

Sometimes stones are there for good reason.

Since an early age, I hated having too many things in my pockets and carrying objects like a camera around with me – perhaps the earliest seedlings of a predisposition to friction-elimination.

I don’t believe in zodiac symbolz and Mercury’s retrograde and crystals and such things, but it’s funny that right around this time of my life someone’s spouse at a work holiday party told me all about “Saturn’s return”, which takes 29 years and “explains” why a lot of people have a really crappy stretch in their late 20s – because that’s when Saturn returns to its original place in the sky from your birth. Of course, this is ridiculous as a means of explanation, and these people are probably the single most egregious offenders of the man-with-a-hammer fallacy. But I would be lying if I said I didn’t ask myself some questions when I suffered a herniated disc as a 28 year old…